- Home

- Rebecca Balcarcel

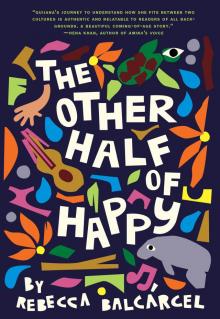

The Other Half of Happy

The Other Half of Happy Read online

TO MY FRIEND DARYL,

who has lighted my life since seventh grade

(1969–2015)

Copyright © 2019 by Rebecca Balcárcel.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Balcárcel, Rebecca, author.

Title: The other half of happy / by Rebecca Balcárcel.

Description: San Francisco : Chronicle Books, [2019] | Summary: Twelve-year-old Quijana is a biracial girl, desperately trying to understand the changes that are going on in her life; her mother rarely gets home before bedtime, her father suddenly seems to be trying to get in touch with his Guatemalan roots (even though he never bothered to teach Quijana Spanish), she is about to start seventh grade in the Texas town where they live and she is worried about fitting in—and Quijana suspects that her parents are keeping secrets, because she is sure there is something wrong with her little brother, Memito, who is becoming increasingly hard to reach.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018037899 | ISBN 9781452169989 (hc) | ISBN 9781452170008 (epub, mobi)

Subjects: LCSH: Racially mixed children—Texas—Juvenile fiction. | Racially mixed families—Texas—Juvenile fiction. | Ethnicity—Juvenile fiction. | Identity (Psychology)—Juvenile fiction. | Brothers and sisters—Juvenile fiction. | Parent and child—Juvenile fiction. | Texas—Juvenile fiction. | CYAC: Racially mixed people—Fiction. | Ethnicity—Fiction. | Identity—Fiction. | Brothers and sisters—Fiction. | Parent and child—Fiction. | Family life—Texas—Fiction. | Texas—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.B3556 Ot 2019 | DDC 813.6 [Fic] —dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037899 ISBN 978-1-4521-6998-9

Design by Alice Seiler.

Typeset in Fazeta and Akzidenz-Grotesk.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

Chronicle Books—we see things differently.

Become part of our community at www.chroniclekids.com.

I LIVE IN A TILTED HOUSE. A bowling ball on our living room floor would roll past the couch, past the dining table, all the way to the kitchen sink. And if the sink wasn’t there and the wall wasn’t there and the bathroom behind that wasn’t there, the ball would roll all the way to my room at the end of the house. That’s what it’s like being twelve. Everything rolling toward you.

“Quijana?” Mom’s voice thuds against my door.

“M’ija,” Dad calls.

It’s not really our house. We rent. But even if the doors hang crooked and won’t close, and even if Mom never comes home till bedtime anymore, and Dad looks tired when he cleans up after supper, I like this tilted house. I get my own room, and there’s a backyard swing. There’s even a stove with two ovens, the upper one like a dresser drawer. We can bake peach cobbler and cheesy nachos at the same time. Like we might today if we weren’t destroying the living room, pulling everything off the walls.

“Quijana, we need another pair of hands, here.”

“Is she outside?”

I wish I were. I’d jump on the swing, pump my legs, climb high, and whoosh through the air. Then I’d sing. It’s my secret favorite thing, even better than peach cobbler. When I sing out there, something rises up my spine and tingles the top of my head. The notes lift me up until I weigh nothing. I could almost let go and sail over the treetops.

Which is another good thing about this tilted house. We can sing in it. Back at the apartment, way back when my little brother was born, Dad would strum his guitar, and we’d sing ballads in English, boleros in Spanish. Then a neighbor would pound on the wall. Or the ceiling. Apartment walls are nothing but panels of saltine crackers.

“I’ll check the backyard.”

No one can tell me why this house tilts. The landlady tried. “That ol’ Texas sun turns dirt to dust. Can’t build nothing on dust.” Mom says it’s the clay soil that’s under the house that slickens in the rain. Dad tells me the builders tried to stairstep a hill, putting each house on a bulldozed shelf. “But no one cheats Mother Earth. She’s remaking her hill, filling in the shelves to make a slope again.” Mostly I don’t notice the tilt. But sometimes, like now, the walk from my room to the kitchen seems steep.

“Quijana.” Dad’s face appears at my bedroom door.

Of course I should be helping. I hang my head. The thing is, those boleros we sing in Spanish? I’ve memorized the sounds. But I don’t know what they mean. And now Mom and Dad are Spanish-izing the whole house.

Dad looks toward the ceiling as if he’ll find a power-up of patience there. Ever since Tío Pancho called and said, “Adiós, Chicago. I got a job in Dallas!” Dad’s been different. He’s playing more marimba music on his phone. He talked me into taking Spanish instead of Mandarin in school.

Last night, Dad went over to help unload the moving van. We’re all going to visit when they get settled. Then I’ll meet the whole family: Tío Pancho, Tía Lencha, and three cousins. They’ve lived in the States for a while now, but we’ve never been able to visit them in Chicago.

The door flies all the way open, and Memito tumbles in. He thrusts a book in my face and climbs on my lap. He thinks my body is a big chair, just for him.

“He wants to read,” I say to Dad. I’d much rather read. A knot kinks in my chest when I think of taking down pictures of me and putting up paintings of Guatemala, the place where Dad was born but I’ve never been. “Can’t we read first?”

“Read afterward,” Dad says.

I start seventh grade in forty-eight hours, so I also want to load my backpack. My folders and notebook paper are still slouching in Kroger bags. They’ll have to wait. I stand up slowly, tipping Memito onto his feet. “I guess we better.”

Dad leaves, but Memito’s bottom lip pooches out.

“I know.”

He waves the book again and stomps his foot.

“It wasn’t my idea.”

His face starts to crumple into a cry. “Ride?” I say. He drops the book as I lift him up.

I hear Mom ask, “You didn’t tell her, did you?”

Tell me what?

He’s almost too heavy, but I hoist Memito over my head onto my shoulders. We march toward weavings and clay pots and volcano pictures—all pretty, but not home. We march up, up, up. Up the hill of this tilted house.

I SET MEMITO DOWN in a room I don’t recognize. The walls are in the same places, but everything on them has changed. On both sides of the TV hang curtains of cloth, each zigzagged with sunshiney yellow and fiery orange. On the bookshelf sit two tall pots with red and green painted animals chasing each other around the sides. Dad leans over the computer desk and hangs a photo of people I’ve never seen before. “My whole family,” he says. I guess he means his parents and brothers and sisters, since me and Memito and Mom aren’t in it.

“Where’d the baby pictures go?” I ask.

Mom nods toward a cardboard box. “They’re online anyway. We’ll make a photo book sometime.”

“Sometime?” “Sometime” always means “never.”

“Hold that side for me, would you, Qui?”

My nickname sounds like “key,” but I’m not a key player or a key factor. I’m not keyed up or keyed in. If anything, I’m off-key, especially today.

I hold one end of the large painting Mom is trying to hang. It’s a lake surrounded by volcanoes.

“Lake Atitlán.” Dad lifts his arms as if he might hug the painting, though it’s too big for that. “The most lovely spot in the world. No importa la distancia, siempre habrá un mismo cielo que nos una.” Looking at me, he translates. “Dist

ance does not matter. Always the same sky unites us.”

“I’m glad we finally framed this,” Mom says. “This room needed a revamp.”

It looks nice and all, but I miss the baby photos and the picture of the Golden Gate Bridge that came from Target. Only Dad’s guitar in its hanger is the same. Memito doesn’t mind; he’s rolling a toy truck back and forth.

“I liked it before,” I say.

“Me too,” Mom says, looking around, “but I always felt bad that this stuff was in boxes. It feels like a new house.”

That was my point.

“Is it time to get out the package?” Dad asks Mom, his eyes twinkling at me.

“Wait right here,” she says. She brings in a white box, the packing tape already cut. “From your Abuela, for your first day at your new school.”

Abuela is my dad’s mom. She sends birthday cards and letters to my parents, but none of our Guatemalan relatives send gifts. We send them gifts, like Crayola crayons that are hard to get there and American-brand jeans.

“Starting junior high.” Dad shakes his head. “I remember my first day of upper school. I wore a new white shirt and polished shoes. At your age, I learned to tie my own tie. Twelve now? You want to stand out and show everyone who you are.”

Actually, I’m hoping to not stand out. To not embarrass myself. Everybody knows that standing out in seventh grade is bad, as in disastrously, monstrously, don’t-be-ridiculous-ly bad, especially the first day. I swallow hard and fold back the cardboard flaps.

A thick, colorful fabric unfolds in my lap. Tropical birds dazzle my eyes. It seems like a tunic or a long poncho. Yellow animals run in a wide stripe across a blue background, and below them, a banner of red diamonds. “Wow,” I whisper. It’s totally beautiful. And totally out of the question. No one in the history of seventh grade has ever worn something like this to school, at least not in Bur Oak, Texas.

“It is a huipil, m’ija, handmade on a backstrap loom. See the birds? Quetzals. They represent freedom, since they die in captivity. You’ll see one on the Guatemalan flag.”

“Dad, I . . .” I look to Mom for help, but she just smiles. “I can’t wear this.”

His face sags.

“I mean, it’s great, but . . .”

“You don’t want to look especial?” Dad’s voice is soft like a velvet balloon and rises at the end.

“Sweetheart, I know it’s not what the other kids wear.” Finally, Mom takes my side. “But . . .”

Or not.

“It could be a conversation piece.”

“A what?”

“Something to get kids talking, asking you questions, getting to know you.”

“Mom.”

“I mean it. Why not?”

I can think of six thousand reasons why not, and thirty of them are going to be sitting with me in each class. Mom is usually more with-it than this. The bright colors must have blendered her brain.

“Try it on,” says Dad. “You will see. You will like it.”

“I do like it.” I run my hand over the cloth, feeling its smooth, close-knit threads. I hate to disappoint them, but I have to. “I just can’t wear it to school.”

Dad steps back.

“Think about it.” Mom puts her hand on my shoulder, then turns to pick up Memito, who is raising his arms.

For a second, a millisecond, I picture walking off the school bus in this outfit. People point and snicker until I’m dizzy just imagining it. I’ve already planned what to wear on the first day, and it involves denim and machine-made knit.

“Maybe later you’ll try on the huipil?” Mom says. “You could wear it next week when we visit your cousins. They’ll be moved in by then.”

I close my eyes. Right. The Carrillos. All born in Guatemala.

Mom puts her free arm around me. “If you wear the huipil to school, people will see how unique you are.” She squeezes me in a half hug.

I’d be unique, all right.

As soon as possible, I tuck the huipil under my arm and slink down the hall to my room, the only unchanged piece of real estate in this house.

I fall onto my bed and look up at my manatee poster on the ceiling. She helps me gather my thoughts. The round body looks comfy and huggable, her eyes patient. I breathe in slowly, hold, and exhale. Okay. Forget the cousins for now. Forget what Mom and Dad want you to wear. Just get ready for school. I make a plan: 1) load my backpack, 2) pack my lunch tomorrow night, and 3) bury this huipil in a bottom drawer.

I tackle number three first.

MEMITO PARKS HIS TRICYCLE by the front door, and a wall of cool air greets us as we step into the house. The four of us walked the entire jogging trail near our house, like we often do on Sundays. September in Texas is still frying-pan hot, so we’re all wearing shorts. We pour glasses of water from a pitcher in the fridge. My hair is still sweaty when Dad says, “We cannot let the lawn die in this heat. Let’s go buy a sprinkler.” I put my shoes back on.

“Take Memito with you, love?” Mom asks. “I need to plan for tomorrow’s class.” She pulls a pot of rice and beans out of the fridge. “All your teachers are doing the same thing as I am tonight.” She winks at me. “It’s kinda fun.”

“What are they doing?”

“Planning what to say, stuff to do in class, homework assignments. All that.”

I think Mom will be a great teacher. I’m almost ready for tomorrow myself. I just need to pack my lunch.

Mom twists a dial on the stove. “I’ll warm up these leftovers. Then I’ll chain myself to my desk,” she jokes. It’s close to true. When Mom gets her master’s degree, she’ll be able to teach college full time. For now, she teaches English in the morning and takes classes in the evening. She comes home late and types on the computer into the night.

Soon Dad, Memito, and I are pulling into the Home Depot parking lot, air conditioner blasting. Inside the giant building, we find an orange-vested man. “Where can we find an esprinkler?” Dad asks.

The man, tall and wide, with thick fingers, squints.

Slowly, my father repeats, “An espr-r-r-rinkeler-r.”

The man shakes his head. “I’m sorry?” The man’s eyes shift to me.

I myself don’t hear my dad’s accent, but other people do, and it’s only around them that I notice it.

My breath catches in my throat. I wince, not wanting Dad to feel bad about his rolled r’s. “Sprinkler,” I say quickly, and the orange shoulders relax. I take Memito’s hand, and we all follow the man to aisle twenty-two.

Sometimes I wish Dad didn’t have an accent. I wish he could be more, I don’t know, regular.

I especially wish he’d been to school here. He doesn’t know the setup, like how we have lockers and metal detectors. Mom knows. She’s a member of the PTA; she knows what student council is. And English is her first language. When she talks to the box at the drive-thru, they get her order right. She knows how things work because, like me, she was born here. Her “sprinkler” and mine is how everything is supposed to be. The English r isn’t fancy, but it’s like a go-to pair of white socks, matching every word I need. The Spanish rrr is orange with pink dots, blinged-out with rhinestones and ribbons.

Dad’s good at other stuff. He knows songs. Guitar chords. Philosophers. He knows Spanish authors like Lorca and Cervantes, but nothing useful.

Even our drive home turns into a college lecture. Memito’s chewing a fruit bar in his car seat while Dad spins a quote around and around in the air. “Listen to Ortega y Gasset: ‘Life is a series of collisions with the future.’ What does this mean?” he asks, almost forgetting a stop sign. “It means we run into challenges—bam-bam-bam!—one after another. When I came to this country, I left behind family, friends. I had to embrace new things, bam-bam-bam! Life is a series of yesses. Yes to everything that comes. You will see this at junior high. Challenge will come, but don’t be afraid.”

“I’ll try, Dad,” I say, though his words are already pulling apart in my mind, floating aw

ay from each other.

Memito falls asleep in his car seat as we turn onto the main road. His neck bends too far, and he looks uncomfortable. But he doesn’t stir when Dad’s cell phone rings through the radio speakers on Bluetooth. He sleeps right through Dad bellowing, “Hola, Mamita!”

It’s Abuela.

Now I’m the one who is uncomfortable. I stuffed her gift into my bottom drawer yesterday, hoping everyone would forget about it. Will I have to thank her? In Spanish? My Spanish is somewhere between tourist and two-year-old.

Dad chats with Abuela as he steers the car under the freeway. Maybe he’ll keep the conversation between the two of them, so I don’t have to say anything. Abuela calls every month, and he always tells her I’m fine. I used to send drawings to Guatemala—stick figures and smiley faces. Now Mom just mails photos. We can’t email, since Abuela doesn’t have Internet.

The closer we get to home, the more I think I’m off the hook. I sit very still and listen while keeping my eyes on passing cars. I hear a word I know, then another—single raindrops in the word downpour.

Dad taps me on the shoulder. “Thank her,” he whispers.

My whole body stiffens. I hear, “¿Quijana? ¿Quijana?”

I clear my throat, my stomach clenching. “Hola, Abuelita.” I add the “-ita” to sugar over the fact that I can’t say much more than these two words.

“¡Mi amor! Qué tal . . .” I’m lost already. She knows I only understand a little Spanish, but her idea of little is big.

She asks “How is . . .” something or other.

I say, “Bien, Abuelita.” Probably true.

“¿Y cómo something else, y I have no idea de tu Mamá?”

My mind blanks and seconds pass. I need to thank her for the huipil, but now she’s asking about Mom. A gap widens between her sentence and the one I am supposed to say next. I wave both hands in the air to get Dad’s attention as we come to a stoplight. In a loud whisper, I say, “I can’t!”

Seconds pass. Abuela asks, “¿Hola? ¿Hola?” like a ringing doorbell.

“Aquí estoy,” says Dad. “Lo siento, tal vez la conexión no está bien.” He covers for me, telling her it’s a bad connection. “A Quijana le gusta el huipil.” He frowns in my direction.

The Other Half of Happy

The Other Half of Happy